In a NY Times story on China's poverty Howard French wrote, on Jan 13, 2008:

When she gets sick, Li Enlan, 78, picks herbs from the woods that grow nearby instead of buying modern medicines. That is not a result of some philosophical choice, though. She has never seen a doctor and, like many residents of this area, lives in a meager barter economy, seldom coming into contact with cash.

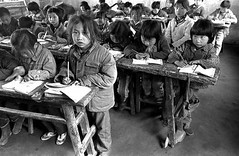

Poor families in villages like Zhangyoufang still struggle to pay the school fees for their children.

Shen Kexia and her husband had to leave their village in Henan Province to find jobs in Hangzhou, a southern coastal city.

“We eat somehow, but it’s never enough,” Ms. Li said. “At least we’re not starving.”

In this region of southern Henan Province, in village after village, people are too poor to heat their homes in the winter and many lack basic comforts like running water. Mobile phones, a near ubiquitous symbol of upward mobility throughout much of this country, are seen as an impossible luxury. People here often begin conversations with a phrase that is still not uncommon in today’s China: “We are poor.”

China has moved more people out of poverty than any other country in recent decades, but the persistence of destitution in places like southern Henan Province fits with the findings of a recent World Bank study that suggests that there are still 300 million poor in China — three times as many as the bank previously estimated.

Poverty is most severe in China’s geographic and social margins, whether the mountainous areas or deserts that ring the country, or areas dominated by ethnic minorities, who for cultural and historic reasons have benefited far less than others from the country’s long economic rise.

But it also persists in places like Henan, where population densities are among the greatest in China, and the new wealth of the booming coast beckons, almost mockingly, a mere province away.

“Henan has the largest population of any province, approaching 100 million people, and the land there just cannot support those kinds of numbers,” said Albert Keidel, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and an expert on Chinese poverty. “It is supposed to be a breadbasket, but there has always been major discrimination against grain-based areas in China. The profit you can get from a hectare of land from vegetables, or a fish farm or oils, is so much more.”

Other experts say Henan and other heavily populated parts of the Chinese heartland are often excluded from the financial support that goes to the coastal areas, and what antipoverty measures there are have little effect. Typically, residents of those areas say, money intended for them is appropriated by corrupt local officials, who pocket it or divert it to business investments.

Paradoxically, they say, they are overlooked precisely because of their proximity to the major economic centers of the east, forced to fend for themselves on the theory that they can make do with income sent home by migrant laborers and other forms of trickle-down wealth.

“Previous poverty alleviation policy focused more on western China, places like Gansu, Qinghai or Guizhou, which were poorer,” said Wang Xiaolu, deputy director of the National Economic Research Institute, a Beijing nongovernmental organization. “Besides, the situation in the border regions is more complicated, because if things go wrong there, it becomes more than a poverty problem. That’s why policy leaned toward them.”

Here in Henan’s rural Gushi County, only 73,000 of 1.4 million farmers fall below the official poverty level of $94 a year, which is supposed to be enough to cover basic needs, including maintaining a daily diet of 2,000 calories. “We should bear in mind that this poverty standard is very low,” Mr. Wang said, echoing the view of many Chinese economists.

Many more people in this part of Henan subsist between the official poverty line and the $1 a day standard long used by the World Bank. The World Bank’s estimate of the number of poor people in China was tripled to 300 million from 100 million last month, after a new survey of prices altered the picture of what a dollar can buy. The new standard was set according to what economists call purchasing power parity. By the new calculations, estimates of the overall size of the Chinese economy also shrank by 40 percent.

Peasants here are the first to tell a visitor that whatever the statistics say, they remain mired in deep poverty. Villagers throughout this county said several recent, highly publicized measures by the central government to improve the lot of peasants had produced only a modest effect on their lives. They included an abolition of agricultural taxes for peasants, the cancellation of school tuition for their children and new pension and health care plans that appear on paper to be more generous for the rural poor.

Since most peasants here have only a glancing contact with the cash economy, the tax exemption is largely irrelevant. Even with the abolishment of tuition, many said, they were still squeezed by a proliferation of other school fees. Similarly, others said, participation fees and deductibles placed the pension and rural health insurance plans out of their financial reach.

“We’re deadly poor,” said Zhou Zhiwen, a 55-year-old woman in Yangmiao whose brick house marks her as better off than most people, who still live in earthen structures. “We grow just enough food for ourselves to eat, with no surplus grain. We don’t have to pay the grain tax anymore, but our lives aren’t much better.”

Asked how she managed, Ms. Zhou said she received help occasionally from relatives who had migrated elsewhere for work. “If people lived well at home, who would want to migrate,” she said. “All of our young people are working elsewhere.”

For many villagers, the central government is out of touch with rural realities in places like this, and the local government is filled with venal officials who shower spending intended for the rural poor on provincial towns and cities or simply take the money for themselves.

“Ordinary people don’t get any real benefits from poverty alleviation programs,” said Li Guangyi, 35, a farmer who lives in the village of Zhangyoufang. “How could relief money get into our hands? It goes first toward relieving the local officials, who get rich on the tragedies of the nation.”

David Dollar, a World Bank official in Beijing, played down the importance of the central government in relieving poverty, saying provincial results had much more to do with the success of local officials in creating an attractive investment climate.

Much of the remaining poverty, he said, involved households that lacked migrant laborers or able-bodied workers. “Very often poverty is related to a health shock or an injury, or the lack of an able-bodied person,” Mr. Dollar said. “Traditionally, the Chinese government approach has been helping the village grow, but if there are few able-bodied people, you have to work on safety net issues.”

In Gushi County, however, even families with members who migrated east for work remained stuck in poverty, and the situation of the migrants themselves often remained precarious.

Shen Kexia, 33, who left her village with her husband for work in Hangzhou, a booming southern coastal city, recently returned home for the birth of her second daughter. She and her husband plan to leave their two daughters with Ms. Shen’s elderly parents as soon as the baby is big enough.

“If my in-laws get sick, we won’t be able to leave,” she said. “We’re home to have this baby because we cannot afford to in Hangzhou, but if we have money, we won’t come back.”

Saturday, January 12, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment