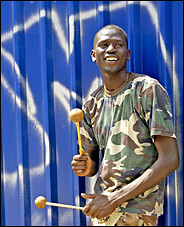

"Ceasefire:" African hip-hop from Sudanese singer Emmanuel Jal / Luz Martin photo

Originally uploaded by trudeau.

Straight Out of Sudan: A Child Soldier Raps

By WILL HERMES

THE consensus among American rappers may be that happiness, as John Lennon once sang, is a warm gun, but Emmanuel Jal is more ambivalent on the subject. Which is particularly interesting given that he spent much of his childhood as a conscripted soldier in the Sudan People's Liberation Army.

"I first held a gun when I was 7," he recalled in August via phone from North London, where he was staying with relatives. "But I didn't fire one until I was 8, when I was in training for the S.P.L.A. Before you fire, you shiver and you shake a lot. But after you fire you become brave and you want to fight even more."

On the forthcoming CD "Ceasefire" (Riverboat, Oct. 11), Mr. Jal raps in four languages - Arabic, English, Swahili, and Nuer - and doesn't mention guns in any of them. The word peace, however, figures prominently. The recording is a collaboration between Mr. Jal, a young Christian from the south of Sudan, and Abdel Gadir Salim, a venerable Muslim musician from the north, and it is partly a tribute to the Jan. 9 peace agreement that nominally ended the bloody civil war in Sudan - a Muslim-Christian struggle that has riven Africa's largest nation in area on and off for decades.

Mr. Jal's story, in its own way, fits into the classic rap paradigm of oppression and transformation. He was recruited by the southern Sudanese militia in Ethiopia, where he and thousands of other essentially orphaned Sudanese children (the so-called lost boys) fled during the 1980's and 90's to escape the war, hoping for shelter and education. After four years of service he met Emma McCune, a British aid worker who became something of a celebrity when she married Riek Machar, the military commander who would later become vice president of southern Sudan. McCune took a shine to Mr. Jal, then roughly 11 (he's not sure of his precise age), and smuggled him onto a cargo plane to Nairobi, Kenya, he said, where a few months later, in 1993, she died in a car crash. Mr. Jal began making music after her death, scored a regional hit (The "I Have a Dream"-style anthem "Gua"), and was soon an international star.

If it sounds like the stuff of movies, it soon will be. Deborah Scroggins's book about McCune, "Emma's War," which touches on Mr. Jal's relationship with her, is being made into a film starring Nicole Kidman. And there is talk about a biopic on Mr. Jal's life. But unlike "Get Rich or Die Tryin,' " the forthcoming film about the hard-knock adventures of the Queens rapper 50 Cent, a film about Mr. Jal could portray an altruistic and deeply religious artist who works with organizations like Amnesty International and War Child International.

Given his background, it is easy to view Mr. Jal as more of a metaphor than an artist - a Christian seeking peace with Muslims, a product of violence who rejects violence, a refugee turned spokesman. In Britain last year he became a cause célèbre with a thick press packet even though his sole recording, the religious-minded 2004 LP "Gua," was (and still is) available only as an obscure Kenyan import. The publicity even helped earn him an invitation to perform in the multicity Live 8 concerts organized by Sir Bob Geldof to raise awareness of global poverty - although Mr. Jal was relegated to a tiny satellite event for African artists that never made the broadcast.

"I met Bob Geldof and he told me I have to sell four million copies of my CD before I can perform at Hyde Park," Mr. Jal recalled, referring to the event's main location in London. "I was thinking someone like me needs to be exposed so people would hear the message I have. And if they like my music, they could buy it - it would be a good chance for practicing fair trade," he added, laughing.

"Ceasefire" is a step toward that exposure. As a collaboration, it is tentative. Because of visa problems, Mr. Jal and Mr. Salim were never in the studio together; the album was recorded piecemeal in London and Nairobi and assembled later. As a rapper, Mr. Jal has a gentle, colloquial flow that switches easily among languages, often in midverse. Songs performed by his group, the Reborn Warriors (like Mr. Jal, many of its members are former child soldiers), gallop lightly and steadily, combining Western and Eastern percussion with synthesizers beneath simple call-and-response choruses and reed flute or sax solos. Things get more interesting on tracks featuring Mr. Salim's ensemble, which rides a seductive 6/8 rhythm known as merdoum that swirls like a desert sirocco, and showcase pungent sax lines that recall the Ethiopian jazz used in Jim Jarmusch's recent film, "Broken Flowers." Mr. Jal tries to find a way into these latter tracks, with only partial success (his nearly spoken-word contribution to "Asabi"); musical dialogues, like political ones, take time to flower.

It will be interesting to see how "Ceasefire" registers in the American market. African hip-hop is a lively, multifaceted scene, and albums by X-Plastaz of Tanzania and Daara J of Senegal have secured distribution in the United States alongside compilations like "Africa Raps" (Trikont) and "The Rough Guide to African Rap" (World Music Network). But most of the scene's output is unavailable outside of immigrant communities, and world-music labels like Nonesuch and Stern's have largely ignored African hip-hop.

"Your average world-music fan doesn't own any Wu-Tang Clan albums," said Ben Herson, a Brooklyn-based producer who owns Nomadic Wax, a label devoted to exposing African hip-hop in America. "And a lot of people see African hip-hop as a corruption of traditional music; for some world-music labels, it might just be too spicy."

American hip-hop, meanwhile, tends toward the xenophobic. But with the explosion of Spanish-rapping reggaetón that may be changing. Mr. Jal said he hoped to work with American rappers in his next project - among his favorites are Nas, the Fugees and Kanye West ("people who have positive messages"). But rap - and music in general, he conceded - is still new to him. "The music I grew up with was bullets and bombs," he said, mimicking the sound of machine-gun fire. "I'm still learning."

Given hip-hop's love of underdogs who have been through the valley of the shadow of death, Mr. Jal may have precisely the background he needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment